I

remember reading, some years ago, that Tolkien had

experienced trouble plotting The Lord of

the Rings, and that he'd "left the Fellowship for a year-and-a-half at

the Bridge of Khazad-dum," or something

to that effect. Smaller talents experience similar problems in lesser degree,

evidently: It took me quite some time to ecide

precisely where Tales of the 13th

Fleet was going… and whether they'd actually succeed in getting there.

As no doubt many of you will recall, not

all of the Fellowship left Moria.

Take that for what it's worth.

Lee said

again with absolute calm, "General, you must look to your division."

Pickett said tearfully, voice of a

bewildered angry boy, "General Lee… I have no division."

-

Michael Shaara

The Killer Angels

USS Athene's crew tensed for battle... and in a way, so did she.

Athene differed very

little from the “name” vessel of her type, USS Akira. She and her sisters had been developed and produced along

with the

Of course, when

your starship is designated a “strike cruiser,” that particular game’s

essentially over before it begins.

A multi-spectral,

high-energy shield grid provided formidable protection, and generous layers of

ablative hull armor, similar to Defiant's,

insulated critical systems in the event the screens failed or were overwhelmed.

Athene's phaser array had been the most powerful

available for starship use when her keel was laid. Even today, it ranked as one

of the heavier primary weapons displacements any Starfleet vessel proffered,

and provided an unobstructed 720° field of fire.

Her magazine held a full complement of Type-VIII photon torpedoes; or, rather,

it had when the war began.

By now, that

supply had been significantly

depleted.

Some irreverent

wit had dubbed her design (and that of the similarly structured Steamrunner-class) "the catamaran," and,

as with most pithily annoying nomenclature, it had stuck. Certainly she did not

strongly resemble the "normal" Federation starship; and this

difference was a point of pride for her proponents even as detractors derided

and mocked the entire design motif, saying "she looks like a warship"—such

tantamount to a ringing condemnation when one considered the source.

Mounted at her

dorsal apex was a mission pod containing the principal torpedo launchers, while

Athene's primary hull housed a "shuttle

bay" more reminiscent of that on a thru-deck aircraft carrier than a

Federation starship. Stored therein were her most notable and distinctive

weapons—a squadron of Shrike-class attack craft. These were in perfect

operating condition, and impeccably maintained—a source of great pride for

their maintenance crews…

…but not

exactly so for their pilots.

Even now, they listened as

one—neophytes, blooded veterans and old hands alike—as their task force

commander spoke briefly on the eve of battle:

"We've learned a lot about the Jem'Hadar over the last few years. I don't have to tell any

of you that they're pretty formidable enemies. I keep hearing endless variants

on, 'They're the ultimate warriors.' Well, I'm here to tell you: That's not

true. The Jem'Hadar are not warriors.

"Warriors forge and hone their

skills… they're not programmed with them.

"Warriors face their fear… and

overcome it. They don't have it bred out

of them.

"Warriors understand that battle is

a means and not an end—that living for war is no life at all.

"Warriors know why they fight; they

don't have to be told.

"Warriors' blood burns hot… and

needs no drug to kindle the flame.

"The Jem'Hadar

are efficient soldiers—nothing

more. In this battle… the warriors are mine.

"Make me proud."

Lieutenant (junior grade) Keith Masters

(call sign "Midas") heard it all through the cockpit's comm

panel, but his thoughts in reaction were probably not what Mantovanni

had hoped to inspire.

Then give us a chance to do that, you pompous

windbag.

He, along with the other members of the

5,517th Tactical Assault Squadron (the "Myrmidons"),

brushed off the "rah-rah" and waited for what really mattered: Their

orders.

They weren't long in coming, and Keith

strained to tell from the tone of his CO's voice whether these would differ

from the others they'd received over the last few months.

Lieutenant Commander Stephen Shaw (call

sign "Achilles") cleared his throat and snapped, "All right,

showgirls, listen up." For an instant, he hesitated, and each

hawk-jockey leaned forward in the saddle, anticipating.

"We're on standby."

The last syllable hadn't even faded from

the speakers before their private frequency exploded with a flood of

infuriated, and indelicate, chatter.

"Son-of-a-bitch…!"

"You've got to be fucking kidding m–…!"

"Damn it, not again…!"

Keith listened silently. Steve'll give it about three more seconds before…

"All right, that's enough. You know the drill: 'Ours not

to question why…'"

They'd all heard that particular line

more than once since the war began, but even Tennyson was wearing thin.

Yeah, but we're not doin'

or dyin',

Steve, Keith thought. That's the problem.

For three months, and over a number of

engagements, the Myrmidons had sat and chafed, their fighters safe in Athene's belly, while the combats raged outside.

Never, on any occasion, had they been called into the fray, instead going from

"standby" to "stand down" time and again.

And so it was this time, too. An hour

later, the "all clear" sounded, and a collection of stiff and sullen

pilots descended from their perches, having followed the battle… but once more

having not participated.

It took a distinctive personality-type

to fly a small attack craft, and there weren't many shrinking violets among the

breed. The grumbling hadn't ceased; and as they trudged into the squadron

dayroom, its tone had become decidedly resentful and, in some cases,

insubordinate.

"I don't give a shit if the

old man is supposed to be a 'tactical genius.'

We're a resource, and we're not being properly utilized. That's

just plain stupid." This came from Lieutenant (junior grade)

Victoria Reston (code name "Nike").

"While I, too, would prefer

participation, I do not believe Captain Mantovanni's reputation is unfounded.

Perhaps there are circumstances of which we are not aware."

Keith rolled his eyes, and thought, Gee,

there's a surprise. T'Virr is supporting

Mantovanni. Never know they were both raised on Vulcan, would you?

Vicki was even less impressed with that

particular stance than he had been.

"Oh, bullshit. It's one of

those philosophical things, and you know it, T'Virr!

Mantovanni doesn't like fighters—thinks they're 'inappropriate to the

modern line of battle,' or some idiotic crap like that—and is ignoring

us! What other explanation could there be?"

Lieutenant T’Virr

(call sign "Artemis") gave a predictable initial response—an arched

brow— and then supported that with a quiet, resolute, "What I know,

Victoria, is based on logic and educated speculation. I do not claim to

understand the source of your… insights."

Keith, knowing Vicki far too well,

stepped between the two women before the exchange could escalate into a

dogfight.

Or would that be a

"bitch"-fight?

Commander Shaw, who was probably in as

good a mood as the rest of his squadron, nevertheless couldn't indulge the

upset, nor allow it free rein.

"All right, catharsis is over for

today. Vicki, stop ranting; T'Virr, don't egg her

on."

The Vulcan protested mildly, "Such

was not my intent." Nevertheless, she glanced back to her debate partner

and offered, "I understand your frustration, Victoria, and to a certain

extent, share it."

Reston reached back to free her mass of

blonde hair from the single pin that had artfully restrained it. She grinned,

grudgingly, and teased, "S'okay… but I

thought frustration was an emotion."

As always, T'Virr

won the exchange.

"Exposure causes contamination… and

I am exposed constantly."

The resultant laughter broke the

lingering tension, and the squadron settled into a more relaxed cool-down.

Eventually, though, the room emptied but

for Masters and Shaw.

The latter decided it an opportunity.

"This is getting worse," Keith

noted, careful to keep most inflection from his tone. He didn't want Shaw to

think emotionalism was tingeing his

opinion.

That fear was unfounded.

The reply was a succinct,

"Yeah."

"You have to do something,

Steve."

"Yeah."

Two for two. Now it gets interesting.

At last, Keith ventured, "Maybe you

should talk to Captain Forrest."

Stephen Shaw proved himself eloquent as

he'd been.

"Yeah."

Luciano Mantovanni leaned back in his

ready room desk chair, seeking a moment's respite from the pile of data-laden PADDs strewn on his desk: Strategic/tactical updates;

long-range sensor sweeps; logistics reports; maintenance/repair dockets;

requests… requirements… demands—an ubiquitous, endless array of

electronic "paperwork" all needing his "immediate"

attention, review and approval.

He closed his eyes…

…and in that instant, of course, the

door chime sounded.

For a few seconds, the idea of simply

saying, "Go… away," held him in thrall.

Eventually, he settled for a slight sigh,

and a murmured, "Come in."

Sera MacLeod's "Good morning,

sir," would have barely registered as a cursory salutation, if he hadn't

detected an undercurrent of disapproval in her tone.

Mantovanni chose to ignore it.

"You have something for me,

Commander?"

The undercurrent became an undertow.

"I do, sir. Other than brief visits

to the bridge and sickbay, you've remained in your ready room for 39 hours and

18 minutes. I must assume that you've been awake and working for that entire

span.

"Logic suggests that you're tired,

hungry…"

"I’m neither."

She arched a brow. "…and,

obviously, irritable."

Mantovanni summoned what he thought

might resemble a reassuring grin.

"Sera, I'm fine. I have a

bed right there," he reminded, vaguely motioning to said alcove, then

gesturing further. "I have a replicator just behind me—all the creature

comforts necessary."

Liberty's operations chief seemed unimpressed

with that.

"'Creature comforts' serve only if

the 'creature' actually 'comforts' itself… or, in this case, himself.

You have never before, to my knowledge, availed yourself of the sleeping

facilities provided for your convenience… and considering that the bedclothes

are pristine, I shall ignore your hope that I would infer their recent

use." An irritated grunt served as confirmation of his none-too-inspired

ploy. "I also took it upon myself to check your replicator logs for the

past 48 hours."

His warning glare gave her only slight

pause.

"You've had three cups of

cinnamon-laced cocoa, the last of which you requested over 17 hours ago."

A hint of acid touched his, "You're

not my mother, Commander; and we both have far more important things to do

than quibble over my eating and sleeping habits."

She inclined her head in seeming

agreement, and acknowledged, "Indeed we do." A moment later, she

continued, "I am, however, taking time from my work because this

task force's captain chooses to ignore the needs and limitations of his

physiology. If you weren't being childish, Cicero, I wouldn't

feel it necessary to 'mother' you."

Mantovanni abruptly realized that he'd

have to throw her a bone, or the conversation could get ugly.

"Your observations and

recommendations are noted, accepted… and appreciated. I promise I'll…

see to my needs."

"No… you won't." When his brow

arched, she hastened to add, "I'm not calling you a liar, but harried

starship captains are well known for pushing themselves unnecessarily—as you

have done. Hatshepsut informed me that she's addressed this with you twice

in the past 15 hours. We have little doubt you mean to take care

of yourself, but we have no doubt you'll continue 'forgetting' to do so:

I had Dr. Aiello run a surreptitious medical scan while you were in sickbay

yesterday; he wasn't pleased with the results. Thus, M'Raav suggested the

action I took ten minutes ago… and both Commander Bagheer and Captain Donaldson

endorsed it, as well."

Suddenly, Mantovanni had an inkling

where this conversation was going… or, rather, had gone.

"And what 'action,' may I ask, was

that?"

Sera tapped her comm badge, and

announced, "You may enter now."

The door slid open and in walked a woman

whose entire being, both appearance and posture, bespoke the phrase "no

nonsense": She was short, and at first glance, a bit pudgy… but a second

look forced Mantovanni to amend that initial impression to "solid."

He silently wagered she'd won more than a few hand-to-hand encounters in her

time—a time that obviously extended some years back, considering her rank.

MacLeod kept the introduction succinct.

"Captain Luciano Cicero Mantovanni…

Senior Chief Petty Officer Ingrid Kepler."

The two continued to evaluate each

other.

"Sir."

"Chief."

Much to Mantovanni's amusement and

dismay, the cool blonde with the even colder blue eyes nodded slowly, as if

having taken his measure, and informed them both, "Don't worry, Commander

MacLeod. He looks tough, but I've… handled

worse."

He got the distinct impression the woman

had been about to say "broken."

No doubt she'd employed the obvious

stereotype to her advantage over the years: Kepler,

after all, seemed the cultivated picture of Germanic discipline. Vaguely, he

wondered where she'd misplaced her riding crop.

Sera, perhaps guessing at his line of

thought, suppressed a grin, and observed, "The chief has been both a cook

and a small arms instructor during her Starfleet career—which eminently

qualifies her to serve as your new steward."

He'd guessed where this had been headed

too late. Still he made an attempt to overturn it.

"Starfleet did away with

stewardship and yeomanry some years ago, Commander," Mantovanni noted

dryly. "You're exceeding your mandate, here."

She easily countered with, "It also

did away with chief science officers and commodores. Yet here I am, serving as

both chief of operations and head of sciences… Commodore."

Mantovanni knew he could win this battle

eventually, but that it would be long, bloody and far too costly. Besides,

though he didn't particularly want to admit it, Sera was right.

"'A cook and a small arms

instructor,' eh?" he echoed.

Kepler didn't hesitate in her response. "Ja."

The captain guessed, "I suppose

that means that if I don't eat…"

"I'll shoot you."

Sera seemed to think that was funny.

Unsurprisingly, Luciano Mantovanni

didn't…

…and, considering her stern expression,

neither did his new steward.

INTERLUDE ONE

Shalra was a Vorta,

and thus had few, if any, vices… but possessed numerous qualities only her

fellows and masters would credit as virtues. She'd been created for the express

purpose of serving the Founders with efficiency and enthusiasm, and had done so

to the fullest extent of her granted attributes.

That didn’t mean, however, that her

faith was blind.

She had once speculated to her fellow Vorta, Sethon, that godhood

didn't necessarily imply infallibility. His horrified expression and response

had amused her.

"You insult the Founders with your…

your…" he'd hesitated, sputtering—incoherent with indignation and

disbelief.

"…blasphemy?" she'd supplied helpfully. "Hardly.

If the Founders were perfect, they would not require servants. I was

made to glorify their divinity with my actions—not sing empty praises

and insult my intellectual betters."

Sethon had bristled at that, but not responded

in kind: The Vorta often measured their relative

competence by the number of clone replacements they'd required. Shalra was the first issue of her genetic matrix and had

lived for almost 120 Terran years—a point about which the only weeks-old Sethon Four had been none-too-subtly reminded. She'd well

known his status as it related to the limited number of duplicates authorized

to all but the most extraordinarily competent Vorta.

And from what she'd seen in the

months since the war had begun, the odds were good that there would be no

Sethon Five. He'd botched the assault against the 13th

Fleet at Teska IV, and it was only Gul Ocett's quick-thinking and

resolve that had enabled even a handful of ships to escape.

Of course, depending on the result of

the subspace communication in which she would soon be involved, there might not

be a Shalra Two,

either: Weyoun might not be a Founder, but his

influence was immense. He had the ear of the Founders themselves. Displeasing

him could mean an abbreviated career or an arrested existence.

As she activated the subspace link and

waited on her superior's pleasure, Shalra took a deep

breath and steeled herself to argue for the continuation of both.

Dukat, leader of the Cardassian Union, smiled

and referred to the PADD he held.

"Let's briefly review the last few

months' happenings, shall we?"

Ocett didn't make the mistake of thinking it

was a question.

"Disruption of convoys in over ten

sectors… annihilation of a strategically significant military service port…

internment or destruction of more freight tonnage than was lost during the entire Tzenkethi War… defeat or

decimation of four deployed task forces… diversion of over 375 vessels

from the front in order to safeguard supply routes and attempt to encircle

them…"

It had been difficult not to cringe. Ocett was well aware of the facts; she'd been present

for too damned much of what he'd just read.

Despite all of it, though, Dukat seemed at ease. The man was still smiling.

Somehow, Ocett

found that less than reassuring.

"This '13th Fleet' has been quite

industrious, I'm sure you'll agree."

There was nothing to be said but,

"Yes, sir." Ocett refused to call him

"Legate" if she could at all avoid it.

"I must admit," he continued, in that patronizing tone

he'd favored since their days as students at Command Academy, "that if

the war weren't unfolding quite successfully everywhere else, your inability to

resolve this little problem would be much more aggravating. As it is,

this has grown from a simple annoyance into a genuine impediment.

"The fact that even a handful of

these ships are still… at liberty… after all this time has boosted morale

throughout the Federation and Klingon Empire. We might have broken them in the

first two months of the war if not for this. They're… how would my friend

Benjamin say it?… 'folk heroes.'"

"Yes, sir."

Ocett had, only a few years before, been the

one on the verge of promotion to legate, while the man she now faced via

subspace had found himself in a political whirlpool—fallen from favor and cast

out of both the Central Command and the Union itself. Governments and

circumstances change, though, and now he stood atop the apex of achievement, at

the pinnacle of fortune… and, she had no doubt, upon the edge of disaster,

resting as he did against the teeth of the Dominion dragon.

"But I've always liked you."

No… you've always wanted me. There's a difference.

"I'm gratified, sir."

"You have a keen intellect."

And a lean body. If I closed my eyes,

you wouldn't even be able to tell me what color they are, Dukat.

"The better to serve Cardassia…" after a moment's pause, she added, "…and

the Dominion."

Only then, and only for an instant, did Dukat's unctuous smile waver.

Direct hit, she thought.

"Perhaps a position on my staff

might suit you."

Retaining her equanimity in the face of that

implication taxed her self-control more than anything she'd ever faced in her

life.

That was… utterly innocuous and

completely vulgar all at once. Some things… some creatures… never change. Don't you

have enough Bajoran woman on which to slake your lust,

Dukat?

She'd had enough.

"I would want to truly merit

such a position, sir—while not leaving unfinished business behind me. Perhaps a

temporary promotion to command all the forces converging in this sector would

allow me to end this troublesome situation."

He knew her intent…

…but would it amuse or anger him?

She was disgusted—with both him and

herself.

Years in the service… promotion to gul… a military record that the majority of

my classmates would give their firstborn to have… and despite all that I’m

playing power and penis politics with a man whose matter-of-fact abuse of his authority is legend

among both Bajorans and Cardassians.

Yet, like it or not, he has the power.

After a moment's thought, his smile grew

even more self-satisfied.

"I think we understand each other, Ocett."

When Dukat's

visage faded from the screen a few moments later, Kirith

Ocett couldn't, at first, decide whether to laugh or

scream.

She was afraid, on both counts, that if

she started, she'd never stop.

***

Sera MacLeod studied the data from her latest long-range sensor

sweep, and contemplated the two-edged sword of superior vision.

Granted, seeing your enemies before they got a look at you was

often a tremendous advantage; sometimes it allowed for devising stratagems

based on what you saw and they didn’t.

On the other hand, when what you saw was overwhelming force you could neither elude nor overcome,

all it did was let you know your worries were justified.

Sera must have noticeably sighed or shifted in response to what she’d

seen, because a moment later, Bagheer’s presence at

her side, and growl in her ear, let her know misery now had company. To most of

the bridge crew, the sound was inaudible, but still disquieting—like an implied

but unspoken threat. Vulcan hearing was extremely acute, though; she’d never

let on, but was usually all too aware of her X-O’s current state of temper.

Or distemper.

Like most creatures evolved from arboreal primates, Sera didn’t

always react well to a predator suddenly on her flank—practically at her

throat. With an effort, she prevented her shiver from becoming a shudder.

“At ease, Commander,” Bagheer rumbled. “Vulcans aren’t on the menu—currently.”

She smiled, and answered with, “Hoping for a policy change from

the Tzenkethi government?”

Bantering with Bagheer was entertaining—if a touch nerve-wracking.

He leaned nearer the ops console, as if examining the data stream, and draped

himself along the periphery of her personal space.

“If necessary, I’ll make policy.”

She could detect the difference between a growl and a purr rather

easily, and when he shifted from the former, her tension instantly lessened.

Clearly he’d noticed her distress… and this concession was as close to an

apology as Sera was likely to get.

Of course, when they settled into examining the data, Bagheer’s growl returned.

This time, she was inclined to growl along with him.

***

“And there’s no way we

can avoid them all.”

Matt Forrest knew he was belaboring the obvious, but frustration

had begun to win past his military bearing: The conversation he was having with

his commanding officer had, thus far, not gone well.

He’d located Mantovanni in Astrometrics,

wandering almost aimlessly through a tactical display constructed from recent

scans of the surrounding sectors. Forrest had always found three-dimensional

maps of this sort a little off-putting; he preferred data on a PADD or a

viewer, so he could brainstorm without feeling like he was in the middle of

one.

That didn’t mean he couldn’t read it just as well this way, though.

It wasn’t good news: There were hundreds of ships comprising seven different assault groups

converging on their position, the weakest of which outgunned them almost

two-to-one.

“What was it you said a few months ago about being ‘a colossal

pain in the ass’?” Forrest had observed. “I do believe that’s the ‘Hemorrhoid

Removal Contingent’ headed our way.”

His commander had simply arched a brow, grunted noncommittally and

continued his musings.

“I’m here to discuss optimal use of my fighter squadron, sir.”

That salutation had gotten a reaction.

“’Sir’?” Mantovanni had echoed. “Should I have you report to sickbay for

an evaluation of your mental state? Inconsistent behavior in a subordinate is

ample grounds for an exam.”

Forrest had grinned. “Not

necessary… Commodore.”

“That’s better.” Whatever warmth the Sicilian’s voice had held seeped

away before he’d added, “There’s nothing to discuss. The fighters are

antiquated, poorly shielded, lightly armed and not exactly what I’d consider

sturdy craft. I can’t see risking their pilots simply to perform the function

of ‘momentary distraction.’”

“It’s what they do,

Cicero. They’re excellent fliers, one

and all; most of them have been in Shrikes

for years—some for decades.”

Mantovanni had folded his arms.

“Their skills aren’t in question, Matt… but the fact some have been flying these ships for that

long is a telling point. They’re older than the Excelsior-class, for God’s sake. From what I’ve read, certain

officers have been recommending replacement designs for them and the Peregrines since the mid-point of the First Cardassian War. Now, here we are, a generation later, still using these

two models as our primary small attack craft.

“Hell, I’ve flown a Shrike-class ship. They have little use

on the front lines. They’re 23rd century technology.”

Forrest had then replied unthinkingly.

“Some people feel the same way about you.”

He’d practically cringed right after saying it, but Mantovanni had

merely smiled, as if conceding the point.

After a moment, Athene’s skipper had ventured, “Their maneuverability and

speed serve to make them less vulnerable than you might think.”

Still, there was no answer.

Matt tried again. “What about…? What about arming them with torpedoes? Not the micros they

have now, but… removing that entire weapons package and swappin’

in a few photons each? That would make them a viable threat to capital ships.

The Maquis

did that with the Peregrines, and

they served pretty well, from what I hear.”

It was then he’d made his observation about the impossibility of

avoiding an engagement.

Now, a few moments later, they were back-to-back, observing their

environment… and watching each enemy task force draw infinitesimally closer by

the minute.

“And I don’t know what you’re plannin’,

if anythin’… but we need the ships—desperately.”

At last, Mantovanni answered.

“Flying a Shrike-class

fighter against Jem’Hadar gunships

is at best a fool’s errand and at worst, a conscious decision to opt for

suicide. I can’t ask them to do that.”

His friend laughed.

“I sometimes forget… you were never really a pilot, Cicero. Many of us possess arrogance to a degree that makes

that of a mere starship captain—present company excluded, of course—seem that

of a well-mannered prep school student. They want to be out there… and not just because they wish to contribute

to the cause. They all know… know…

that they’re not going be the one to

buy it fightin’ the Jem’Hadar.

They’re too good.”

He summed up his argument. “So… we need the ships… they want to be

involved… I think they can contribute. Have I missed anything?”

“You haven’t used ‘Commodore’ in a while.”

Forrest suppressed a chuckle, but smiled again. “Forgive me… Commodore.”

“Your recommendations are noted, Captain.” The tone was final, and

for a moment, Matt had no idea whether he’d gotten through or not.

After Mantovanni told him his plans, he still wasn’t sure.

***

Bela Tiraz wasn’t an overly expressive man…

but that was not at all to say he was emotionless or even uncaring.

Understatement simply seemed to fit him as well as the carefully tailored

uniform he wore. A crew often takes on

certain of a commander’s characteristics—following his lead, as it were—and

that of Ptolemy was no exception.

They had fun, and quite a bit of it… but it was usually quiet and dignified, like

their captain.

Over the last few months, that quietude

had become even more determinedly purposeful, as if a concerted silence might

enable them all to escape the Fates’ notice.

Thus far, it had worked. Casualties

aboard Ptolemy had been light—a few radiation burns, a couple of broken

bones.

The ship herself, though, hadn’t fared

quite so well; and his X-O’s report told Tiraz her

ongoing recovery was, in some ways, still slightly more of a convalescence.

“Again

that same problem?” Bela inquired.

“Indeed,” Suvak

replied. “The damage we took at Teska IV, while not

extensive, has been exacerbated by subsequent combats. Lieutenant Michaels’

repairs, though imaginative, have been only marginally successful. He describes

the primary generator as ‘functional until someone gives it a dirty look,’ and

the auxiliary as…” he paused, and Bela steadied

himself for one of his chief engineer’s ‘Michaelisms’

“… ‘twitchier than a virgin at a beach house after the senior prom.”’ Suvak took refuge in an expression of Vulcan dignity,

almost implying he didn’t quite understand that last metaphor. The slightly

arched brow and intimation of a smile, though, put that idea to rest.

The amusement was momentary, though,

and almost immediately washed away by cold reality.

“In other words, we could suddenly find

ourselves without aft shields during the next firefight.”

“Unfortunately, true.” It was rare for Suvak to assume the role of apologist, but he did, with,

“They would certainly have been replaced at a dry-dock, had we access to one.

Unfortunately, such facilities—along with time and non-replicable parts—are at

a premium. I consider it a remarkable effort that it is functioning as well as

it has, in light of our current situation.”

From tactical, Selennia

Vox volunteered, “I’ll play some more with the

distribution grids on the other generators; they should be able to partly

compensate for our problems with shield six. The structural integrity field

could probably also spare some power.”

Tiraz nodded... but his frown didn’t disappear.

His engineers knew their jobs, and

would have done whatever was feasible or

possible, with even a bit of the impossible

thrown in for good measure. Pride would not have prevented them from plumbing

their bigger sisters for whatever supplies or assistance could be gotten or

scrounged… but each ship had its own problems, each staff its own repairs… and

ultimately, you did the best you could with what you had.

And their best had still left Ptolemy with a noticeable, exploitable

weakness. Stopgap measures were all well and good, but….

He told Suvak,

“Make certain Captain Mantovanni is aware of our… continuing situation… so he

can factor it into his strategy for the upcoming engagement. This is going to

make our withdrawal somewhat more problematic.”

The Trill, Vox,

attempted to lighten the moment again.

“Already planning our retreat, sir? The

battle hasn’t even been fought, yet.”

Bela said nothing, because he knew captains weren’t supposed to

express such sentiments as he’d just had.

Either way… I don’t think it’s going to be much of a fight.

***

Once again, Stephen Shaw had a duty to which he wasn’t looking

forward—at all.

“I’ve got good news… and I’ve got bad news.”

He glanced around the squadron dayroom, and briefly examined each

pilot in turn. They’d been disappointed so often he wasn’t sure whether the

phrase “good news” had even registered—though he was certain “bad news” had.

“We’re off standby, Myrmidons. We fly in this next battle.”

It took a while to penetrate… but the murmurs of relief, approval

and even enthusiasm gave way immediately when Lieutenant (junior grade) Laura Molitor (call sign “Atalanta”)

asked, none too gently, “So what’s the bad

news?”

Sugar-coating wouldn’t do any good, Shaw knew.

“Only six of us will pilot.

The rest will navigate and handle ops for the fliers: Two-man crews.”

The grousing soon gave way to sidelong looks, as the 5717th’s

members immediately began sizing each other up. Shaw watched in fascination as

Lieutenant Aliarra Sih’tarr’s

antennae each made an independent circuit of the room—almost like a personal

sensor sweep—before reorienting on him.

“And which of us,” the Andorian woman (call sign “Rhea”) asked,

“will actually fly?”

That opened the floodgates.

Everyone had an opinion; and, of course, their method of choice

invariably favored themselves in some fashion. Shaw heard, in rapid succession,

most experienced (this from the four or five who’d been doing this the

longest), highest-ranked (Sih’tarr pointing out that

“Rank hath its privileges”), lowest-ranked

(“After all, you guys are too valuable

to risk,” Ensign Davor countered) and even all-female

(this half-jokingly, or at least he hoped so, from Vicki Reston).

Shaw once again, as he had when hearing about the method of

deployment, toyed with the idea of drawing lots. He had twelve great pilots and

didn’t want to offend—or worse, damage the all-important ego of—any. He wasn’t one to shirk responsibility,

though... and while they were all talented, some were just a hair better.

“Athene… Nike… Rhea… Midas… Hector…

you’ll fly—along with me. Pick a re-up who works well with you. We’ve all been

paired off with each other dozens of times in sim, and during exercises, so there shouldn’t

be any personality conflicts.

“Pre-flight briefing at 1700 hours, so tactical prep complete

before then.

“And those of you who aren’t flying… don’t take it personally.”

He didn’t know why he’d said it. He did know it hadn’t done a bit

of good… because in their place, God knew, he’d have taken it to heart.

Stephen Shaw silently cursed at Maitland Forrest, Luciano

Mantovanni and the gods, for having forced him to cut his beloved squadron in

half.

He knew they’d never be the same.

***

Dukat was beaming… and, as a consequence, Ocett

was uneasy.

“Kirith,” he said reassuringly, “you’re entirely too hard on

yourself. I’m actually…” and he paused for emphasis, “… quite pleased with you.”

The fact that

he was employing her pet phrases wasn’t exactly reassuring.

“You’ve more

than earned a position here at Terok Nor. I must admit, I’ve been imagining us

side-by-side, striving towards a mutual goal… and achieving it together.”

He

leaned forward, and Ocett almost drew away from the

screen. Even through a viewer, from dozens of light years away, Dukat’s combination of oily charm and unwelcome

suggestiveness seeped through her façade of indifference, and it was all she

could do not to shudder.

The

cliché was entirely accurate: The man made her skin crawl.

Still,

he was her superior—if not intellectually, then politically—and she owed the

rank and uniform respect.

Some

part of her, though, found strength from indignation, and Ocett

delivered a smile she was certain wasn’t the kind for which he’d been hoping.

“While I

imagine that could be quite rewarding, I do have unfinished business here. There are yet four enemy vessels

at large… and, once again, that rabble

gave better than it received: Gul Jevar

lost two of five cruisers and nearly a squadron of Hidekis, in exchange for a single

starship and a handful of fighters.”

Cardassia’s leader replied with a dry, impatient, “I have eyes, Kirith;

I read the report.

“But according to Jevar’s

account of the battle, one of the remaining four is limping badly, and two

others are damaged beyond repair, short of their commandeering a drydock—which I assume will not occur.”

Behind

him, Dukat’s hulking shadow, Damar,

grinned at the implication of her incompetence.

As if you

would have done any better, you brutish imbecile. If I recall correctly, your idea of subtlety, Damar,

is drinking from the glass instead of the bottle.

“No, sir,” she hastened to reply. “Even with Liberty fully operational, they lack the

firepower to overwhelm even the most lightly defended facility in either this

or the surrounding sectors.”

That restored Dukat’s

humor.

“Then

their effectiveness as a battle group is essentially past. All they can do is

attempt to reach the Federation border, make one last, futile attempt at a

convoy… or hide like a clutch of voles.”

Ocett’s reply wasn’t as emphatic as perhaps it should have

been… but Mantovanni had burned her once too often.

“That is my

preliminary assessment as well.”

Dukat cocked his head, still smiling.

“‘Preliminary assessment.’

“Well, then, I suppose I should allow you time to

make a final assessment, shouldn’t

I?”

His

face changed; and for the first time, it displayed that studied malevolence for

which he was known.

“Finish them quickly, Ocett.

Even my patience with an old

friend has limits, and this little vermin hunt has grown tiresome. Your future

is still a bright one, but you must take hold of it… and the ‘13th

fleet’ is in your way.

“They’re

almost helpless. Find them, and destroy them—for Cardassia...”

She

waited for the inevitable conclusion of that statement… but it never came.

Instead, he made it more intimate, and frightening.

“…for

yourself… and for me.”

The

transmission ceased, and she watched the screen as a Cardassian insignia

replaced the face of a man who clearly thought himself the personification of Cardassia.

Shalra, who had, as always, watched the interaction in

anonymous silence, placed a hand on her shoulder.

“His usefulness

will end, Ocett. He is the type of monster that

eventually devours himself.”

Ocett nodded, and sagged back into her seat.

“The question, Shalra, is whether he’ll devour me first.”

***

Matt Forrest

was angrier than he’d been in a long time, and sick at heart, as well.

Before him in

his ready room stood a quartet of exhausted, demoralized, embittered officers…

and he knew the next few minutes probably weren’t going to improve anyone’s

outlook.

As a matter of

fact, the future was looking pretty damned grim for all concerned—including him. Still, he resolved to

remain professional and impartial—frosty.

Perhaps there

was a resolution to this situation he hadn’t seen.

“You know,” he said, allowing his drawl to become

more pronounced, “I’m known for what I’m told is a fairly relaxed command demeanour. People say I’m easy to talk to—that Athene is what

they call ‘a happy ship.’” He flashed a glance at his X-O, but there was no

help there: Maria looked as

distressed as he felt… and her

expression told him the approach he’d taken sounded like rambling.

That’s probably ‘cause it is ramblin, darlin’.

Two of the

four, both rigidly upright, were beginning to look a little pale.

Irritated, he

snapped, “At ease. I don’t want any

of you faintin’ from lockin’

your knees—at least not until I’m done.”

Briefly, he

reconsidered his approach.

“I went to bat

for y’all over this,” he announced, rather matter-of-factly. That tone lasted

for all of two seconds. “Please tell

me I did the right thing—that there was a damned

good reason for what happened three hours ago.”

One, for an

instant, averted her eyes, and actually shuffled her feet.

For

some reason, it was enough to provoke his temper. He pitched headlong off the

careful, too-thin tightrope of patience he’d been walking, and found himself

just short of a full-blown conniption.

“Ensign, do I have your undivided attention!?”

Even

Petrova flinched; she’d never seen, let alone heard, him in such a state.

“Sir! Yes, sir!” the girl replied, stiffening

back to attention, eyes bright with something that might have been either fear

or anger.

Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.

“Good. Because I’m going to ask you a

series of questions… and you will answer them to my full and absolute

satisfaction—with alacrity. Do you

understand?”

“Aye, aye, sir!”

“That’s two-for-two, Ensign. You’re off

to a flyin’ start… but they get more difficult from

here.” He drew a long breath, then exhaled; it felt like he was letting half of

it out through his ears.

“Now… why in hell did you break formation?”

***

Stern glares of

coercion… eloquent, emphatic gestures… and that Stentorian voice—a voice that been

described as having two distinct tones: “Donner und Blitzen” and “Gotterdammerung”—all were impressive

weapons in Ingrid Kepler’s arsenal. And in pursuit of

her primary duty—to make certain her commanding officer took proper, or at

least better, care of himself—she had employed them all liberally, with a

middling measure of success.

Now, though… no

one would have recognized her.

She set the

tray down on the desk, and moved to stand next to him as he stared through the

ready room view port—seeking answers, or perhaps solace, in the void.

Gently, Ingrid

set a mug full of broth in his hand. Much to her surprise, before she could

command, or even cajole, he absently drew it to his lips and took a sip.

“Plomeek,” he murmured.

There was a

touch of approval there, she noted.

The slight

smile it had evoked, though, was gone an instant later.

“Do you have

children, Ingrid?”

He’d surprised

her with that.

“Ja,” she answered.

“One son, one daughter… and currently, one starship captain.”

This time, the

grin lasted a little longer… but it, too, soon faded.

“What would you

want to hear from their commander if they’d…?”

She risked a glance at his desk.

So that was it.

He was attempting to compose letters of condolence. Ingrid knew

Mantovanni was the kind of man who would agonize over every word in each one…

and that the mere idea of form letters, even ones personalized with a few

specifics per casualty, would be to him, dereliction of duty—at best.

“Other than one letter in particular, sir, wouldn’t the responsibility

b–”

“The commander,” he interjected, “is recovering from injuries sustained

during the battle. This, unfortunately, falls to me.”

Falls on you, you mean, thought Kepler, frowning. Along

with everything else, it seems.

“I have your permission to speak freely, sir?”

“Always.”

“Good.” She folded her arms, again becoming the quintessence of maternal

formidability.

“You’re a great starship captain and a superlative tactician… but as a

high-level administrator…?” She shook

her head disapprovingly. “Being a fleet commander, sir, does not mean micromanaging. You’re not qualified to write these letters;

you didn’t know most of these people. Also, it’s not critical this be done now:

We’ll not be delivering them any time soon… and by then the person who should do it will be back on her feet

and capable of shouldering this.

“It may not be pleasant… but it might just be cathartic.

“In addition… I’m not sure she’ll appreciate what you’re doing here,

either.”

He stiffened.

“I’m trying to make things easier for her.”

Kepler was undeterred: He was hearing her… he was even listening… but recent

events had left them all reeling, and, in many ways, as their leader, he had a

share in everyone’s uncertainty.

This, though, was something he could do;

and he had latched onto it.

Unfortunately, in Kepler’s view, it was the wrong thing to do.

She gave careful thought to her next words… but decided to proceed.

“You asked what I’d want to hear in a letter like that.”

That focused his attention even further.

“I did.”

“My answer is this: Exactly what I did

hear—that my husband had fought bravely, that he had many friends who missed

him and that his actions had made a difference. And I heard it from someone

who’d known him, who’d fought alongside him, who’d seen him fall—someone who

could recall a friend, rather than eulogizing a stranger.

“It made a difference to me.”

She could sense he was about to offer sympathy… and that brought her

back to the here and now. Before he could speak, Ingrid offered a suddenly

brisk, forbidding, “If you’ll excuse me,

sir,” and headed for the door.

Before it opened, she gestured to his mug. “Now finish that.”

Both their smiles were grateful: His for what she had said…

…and hers for what he hadn’t.

***

Keda’ratan was that rarest of Jem’Hadar Firsts:

One whose relationship with his Vorta was not

antagonistic, or even adversarial.

Calling them friends

would have been going too far… but, certainly, they worked together admirably well.

Shalra had numerous Jem’Hadar

under her command, but unlike many of her ilk, she had always relied upon Keda’ratan’s military acumen and his unerring way with the

men.

For a Vorta, her sight was unusually

keen.

When last they had spoken, though, their... association… had almost taken a turn for the worse.

“You will allow the Cardassians the lead position in this battle,”

she had said.

For a moment, he had almost balked.

“We are the Jem’Hadar. We are the

vanguard; it is our right according to The Way of Things.”

“It is also The Way of Things,” she had replied, “that the Vorta command and the Jem’Hadar

obey… but you are The First, and I defer to your judgment.”

Before he could speak again, though, Shalra

had explained her reasoning—at length.

He, much to his amazement, had found it sound—both tactically and

strategically.

“Very well,” he had conceded. “We shall proceed as you recommend.”

She had nodded her satisfaction and terminated the transmission.

Now, days later, as Keda’ratan completed

his annotations to the sensor logs recorded during the battle and prepared to

transmit them, he again marveled at his continued good fortune. For two years,

he had been a Revered Elder… and rather than placing him at the forefront of

some engagement, in hopes that he would die and give way to a more easily

manipulated First, Shalra had instead made him more

of an attaché and advisor. He still engaged in battle—he was Jem’Hadar, after all—but she had not betrayed, abandoned or

even wasted him. To her, he was more than a commodity.

He was an asset.

From a Vorta, that was indeed a

compliment.

Victory is life… he thought, and depressed the Send

button.

…and life is good.

***

Starfleet memorial services for lost

vessels were usually crowded affairs.

This one, though, was an exception. It

wasn’t that the living had no regard for the dead—far from it. In this case, it

just meant the former were overwhelmed with work that had to be done, and soon, if they actually wished to stay living.

The survivors, in other words, were

focused on surviving.

It didn’t help matters that there were no

deceased over which to mourn: The “13th’s” escape from the scene of battle had

meant leaving the bodies of those lost to their fate… and that was bitter

fruit, indeed.

Each captain attended. Even together with

those retrieved from the dying ship before her end, though, they seemed a mere

handful—so few mourners for so many dead.

The seven survivors had chosen a single

representative to speak for them… and from her expression, it was a duty she’d

accepted reluctantly.

“We all understand that people die during

a war.

“But we also think it’ll be those other people… and barring that, hope

that it won’t hit so close to home: Better a stranger than an acquaintance…

better an acquaintance than a friend… and better a friend than someone you…”

she hesitated, and then stressed the last word, “…love.”

“You see, I know what my captain thought

when he died, because I knew him.

“He thought, ‘Better me than them.’”

Selennia Vox had meant

to continue, but she faltered, then. Joined Trills saw far more death than most

over the course of their myriad lives, and many assumed they possessed an

advantage in dealing with such things—that it got easier.

After seeing her in that moment, though,

everyone present knew one thing.

It never

got easier.

When Luciano Mantovanni had finished his

briefing, two of the three captains present in the ready room were agitated. Liberty’s commander briefly wondered whether he was losing his touch: Usually, by

this point, he’d aggravated everyone.

Erika Donaldson, at least, seemed to find his opinion as agreeable as she

always had.

“You can’t do that!”

For the first time in a long time, Matt Forrest agreed with her.

“While I usually, eventually,

come down on your side in these discussions, Commodore, this time….”

His drawl had become even more pronounced.

Krajak, at least, supported him—though that wasn’t surprising considering

the decision he’d just announced.

“It is reasonable,” he proclaimed… and when Erika shot him a glare, bared his teeth in a

casual sneer.

She looked singularly unimpressed.

“‘It is reasonable’… this from

a Klingon eager to die in battle. Now there’s

a ringing endorsement.”

In reply, Krajak flexed his fingers, as if

looking to loosen the fit in his leather gloves. The message—that he’d briefly

toyed with the option of wrapping them around Donaldson’s neck—wasn’t lost on

any of them. While it wasn’t precisely an idle

threat, though, it wasn’t a serious one, either.

More like the Klingon

version of catharsis, Mantovanni thought.

“Captain Donaldson,” he said, “wasn’t it you who just a few months ago

recommended we make for the border instead of fighting? Well, now you’ve got

your chance to do just that.”

Now she looked even less

impressed.

“That was the Federation

border,” Donaldson countered, “not the

Tzenkethi!”

The Sicilian arched a brow, and afforded her a slight smile she didn’t at

all appreciate. “Semantics.”

Before she could further express her indignation, he continued, “We’re

out of alternatives. Your ops chiefs’ damage assessments make clear that both Adventurous and Athene are barely warp capable, let alone combat ready. Ch’Moch can cloak, her weapons systems are

fully operational, and she’s now faster than either of the other two vessels

still… under my command.”

Mantovanni couldn’t believe he’d almost said, “…in one piece.”

Donaldson pointed at him, and waved to include Krajak

in the gesture.

“You haven’t explained where you

two are going while we limp

towards evisceration at Tzenkethi hands.”

“Paws,” Forrest corrected, and earned himself the nastiest look Erika had

yet leveled.

At least she’s

distributing them evenly, Mantovanni thought.

“No,” he then agreed. “I haven’t.”

The subsequent silence let them know he had no intention of doing so.

Forrest smiled.

“Don’t be upset, Cap’n Donaldson. We’re

obviously now on a ‘need-to-know’ basis… and as we won’t be a goin’, we don’t ‘need to know’—especially since it’s a plan

of which Krajak approves.”

The Klingon offered a toothy confirmation.

Usually, Matt Forrest’s gibes found their way unerringly beneath

Mantovanni’s skin, but today they missed their mark. He ignored the invitation

to rebut, and instead added, “Commander Bagheer will accompany you aboard Athene, which

will be lead ship during Liberty’s

absence. Please give Captain Forrest the same respect you’ve always… hmm…” Mantovanni reconsidered his

statement. “Please afford Captain Forrest the respect due his position, Captain Donaldson.”

It lightened the moment. Forrest chuckled; Krajak

laughed openly. Even Erika, though her cheeks brightened, took it as it had

been intended, and offered a sheepish grin.

Mantovanni replied with that spectral smile, and a crisp, “We’ll see you

at the rendezvous.

“Dismissed.”

Forrest lingered, though, as Mantovanni knew he would.

“You read my report concerning our last engagement—specifically as

pertains to my pilots?”

“I did.”

Athene’s skipper came around the desk and found his way to the window—precisely

where his CO had been spending much of his recent time.

“I’ve held off on any disciplinary action pending an opinion from ‘on

high.’”

Mantovanni nodded.

“I might have done the same thing, Cicero, at that age, in that

situation.”

Again, he received a nod and nothing more.

“Do you want me to handle it?”

At last, Forrest got an answer.

“No. Tell them…

“…tell them we’re all living

with our choices… and that any disciplinary action will wait pending a return

to Federation space. I’m not about to speak ex

cathedra or turn over a drumhead and render judgment on this.

“I kept them grounded. I let them loose.”

I take the blame.

Now Forrest asked the question he’d dreaded.

“What about their flight status?”

The question had caught him by surprise, and Mantovanni actually

laughed—a brief, harsh sound more like a smoker’s cough.

“If I’ve got to keep doing this…

so do they. Restore them to active duty… your discretion on their missions

until I return.”

“Yes, sir.”

He really had nothing further to say, but for a few moments, Matt

Forrest held his ground, wondering whether he would see this man again.

“At least we got away, Cicero. That’s a victory, of sorts.”

For a moment, he thought Mantovanni might say, “Tell that to Ptolemy’s crew,” but he spared them both

that.

Instead, he found something better, and worse.

“‘Another such “victory”…’”

Forrest knew the reference well enough to finish.

“‘…and we shall be undone.’”

EPILOGUE

Excerpted from Jane's Fighting

Ships, Special Edition:

Naval Engagements of the late 24th

Century:

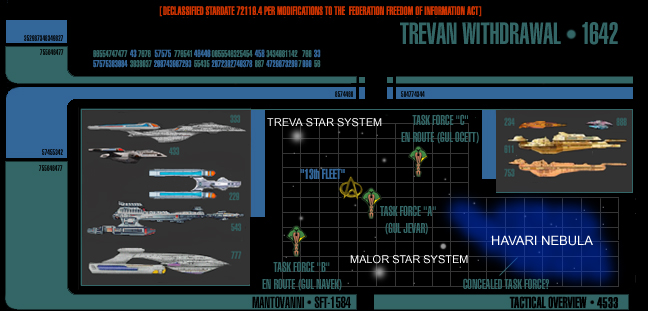

Most naval historians of note long

considered the decision to fight at what has been designated the Trevan Withdrawal one of the few strategic missteps of

Luciano Mantovanni’s long career. Until that point, Mantovanni had taken care

to deploy only when possessed of numerous tactical advantages, the element of

surprise or both—thus adhering to solid principles of engagement.

Yet despite at this time having neither

of these, the “13th Fleet” challenged a numerically superior Cardassian force,

commanded by a competent leader in Gul Jevar; and while the results of the engagement were

favorable insofar as absolute losses in ship tonnage, Mantovanni’s beleaguered

battle group could ill afford any

loss by this point of the war.

In addition, the encounter had been

deemed by these selfsame experts not only unnecessary, but easily avoidable.

One of the Federation Alliance’s few technological superiorities throughout the

Dominion War was a distinct speed advantage: While Cardassian and Jem’Hadar vessels labored to achieve warp

nine-point-six-five, for many Starfleet and Klingon ships this was a

sustainable velocity. Mantovanni had exploited this for months, eluding pursuit

and denying his foes the decisive meeting they were now desperate to attain.

Clearly, then, standing their ground in this instance was deemed to have been

foolhardy at best… or, worse, a blunder that could have cost thousands of

lives.

The judgment of history, however, is

rarely final, in that new evidence requires a reevaluation of perspectives long

considered inviolate. The 50th anniversary of peace with the Dominion brought

with it the long-awaited declassification of uncounted gigaquads

in data—a literal treasure trove for scholars in which to happily wallow… and,

occasionally, surface with information calling into question theories long

accepted as “facts.”

Mantovanni’s renowned tactical

sleight-of-hand and famed reluctance to speak with either journalists or

biographers had led to specious conclusions being drawn as to the motivation

behind his decision. While most had believed it a simple error in judgment, a

few detractors had even gone so far as to accuse him of hubris—that his unprecedented successes behind enemy lines had

caused him to believe his “generalship” irresistible, a la an even more famous commander, Robert E. Lee, whose

ill-considered deployments at the Battle of Gettysburg in all likelihood

changed the course of American history.

Long months of sporadic but intense

combat, though, had taken their toll on the “13th Fleet.” Despite brilliant and

heroic measures by the engineering staffs on each vessel, three of the five

remaining ships had begun to show the strain: Hull micro-fractures caused by

repeated weapons fire and near-constant use of high warp (problems which would

have been a simple matter to repair in dry-dock) became causes of serious

concern.

Thus, Mantovanni’s options were not palatable: Attempt to avoid each of

the three task forces bearing down on them with a series of high-warp evasive

maneuvers that, while successful until that point, now ran a serious risk of

catastrophe aboard one or more vessels, bringing all three opposing units upon

them simultaneously; or select one enemy battle group at random, attempt to

cripple it, and escape through rather

than around.

Liberty’s commander

chose the latter.1

Jevar’s command, while not inconsiderable, was

the smallest of the three pursuing the “13th.” It numbered two heavy Keldon- and three

medium Galor-class

cruisers, these supported by 14 fighters (a dozen Hidekis and a pair of Jem’Hadar “bug” ships). It was an essentially Cardassian force,

employing Cardassian tactics, and Mantovanni utilized that to his advantage as

best he could.

Despite their numerical inferiority, the

“13th” assumed an aggressive posture. For the first time since the war had

begun, Mantovanni ordered USS Athene’s commander, Maitland Forrest, to deploy that

vessel’s squadron of Shrike-class

attack craft, and split it in two: The first flight of six provided cover for

the two most vulnerable starships, Adventurous

and Ptolemy; while the second assumed

the point.

Taking a page from the Jem’Hadar school of tactics, the six lead fighters, stuffed

with antimatter and remotely guided, swept in for a kamikaze run on their targets, the Keldon-class vessels. Caught by

surprise at this decidedly un-Starfleet like maneuver2 neither

ship’s point defense reacted with the swiftness and efficiency necessary, and

each took a direct hit—knocking out their warp capability for the battle’s

duration, and some days afterward.

Meanwhile, the “13th” opened fire on the

Galor-class

starships, concentrating attacks on enemy nacelles, and immediately put one of

the three in a condition similar to its Keldon brethren: Still combat-capable, but going nowhere

fast.

The Cardassian reply was immediate, and

also cannily directed: Instead of concentrating their attacks on the heavily

armored and shielded Liberty (a

tactic that had cost them valuable time at Teska IV)

they instead hit hard at the three other Starfleet vessels, inflicting moderate

damage on each.

The Hidekis swarmed about, harrying Liberty, nagging at Ch’Moch and attempting to strike

at USS Ptolemy’s vulnerable aft

quarter, where her shield generators had begun to flicker under the strain of

combat. For a time, the Jem’Hadar fighters remained

at a distance observing, which, according to eyewitness accounts, was a source

of significant anxiety and confusion to the Federation side.

The remaining Shrikes’ role at this point was critical: Ptolemy was essentially shield-less to the rear, and Adventurous not much better off. When

one of the Jem’Hadar fighters entered the battle,

making a run for Adventurous that

seemed an attempt to ram, one of Ptolemy’s

protectors peeled off momentarily to engage it, trusting that his fellows could

handle the role as literal screeners for a few seconds.

It was an understandable mistake… and

the opportunity for which the Jem’Hadar had

maneuvered. The second fighter slashed in past the desperate cover fire of the

two remaining Shrikes… and, its nose

nearly on point with the larger vessel’s shuttle bay, slammed into Ptolemy’s secondary hull.

Incredibly, the doughty little Nova-class held together for almost ten

seconds—enough time for Liberty’s

pilot to execute a roll that brought the two ships belly to belly, where she

matched speed, lowered shields, beamed away all the survivors she could and

accelerated into warp milliseconds before Ptolemy’s

warp core breach.

By this time, Mantovanni’s plan had been

partly successful: All five of the opposition’s large vessels had some sort of

damage preventing use of their warp drive (two were so injured the decision was

later made to scuttle them)… and the “13th” fled the scene, the Hidekis in hot

pursuit. Over the next few minutes, these were whittled away one by one… but

not before inflicting such harm as made both Athene and Adventurous wounded to the point of uselessness.

The numbers had favored the “13th,” but

the reality of the situation was grim. Five vessels had, for all intents and

purposes, become two… and drove Luciano Mantovanni to a decision the consequences

of which even half a century later he is probably still best known—at least to

Cardassians.

- James Herriford

FOOTNOTES

1 – To this day the Cardassian Union, despite increasingly warm relations

with the Federation, is notoriously reticent about releasing any war-related

materials for public dissemination. After repeated inquiries, though, Central

Command historians finally confirmed that at least four more task forces were

converging on the “13th’s” position from beyond Liberty’s sensor range.

2 – Hindsight indicates that Jevar should have

been prepared for something of the sort: Mantovanni had used a similar tactic

at Teska IV, employing the otherwise near-useless Oberth-class USS Lowell to bring down the shields on a

Dominion battle cruiser. Still, Jevar indicates in

his memoirs that “this flagrant disregard

for Starfleet engagement protocols startled me, especially since the craft

employed had been undamaged when the maneuver was executed.”