As with most true Trek

fans, I have a particular reverence for the original series and its characters;

however, that doesn't mean I think nothing more can be said about them.

Besides, the legends of yesterday must somehow pass their wisdom onto those of tomorrow...

and thus pave the way to a brighter future.

This incarnation of Peter Kirk appears courtesy of, and inspired

by, Trek fanfic

legend Rob Morris.

Oh… and a reader’s compliment necessitated this disclaimer: I didn’t

create the joke you’ll encounter early on in the narrative, but, rather, heard

it repeated on ER some years ago, and

believe it’s been around for decades—public domain, as it were. Peter David

also used it, I believe, in one of his New

Frontier stories… but since he’d obviously swiped it, too, well… I feel no

guilt.

Clearly they’re still using it in the 23rd century.

“Winning the Exchange”

By Joseph Manno

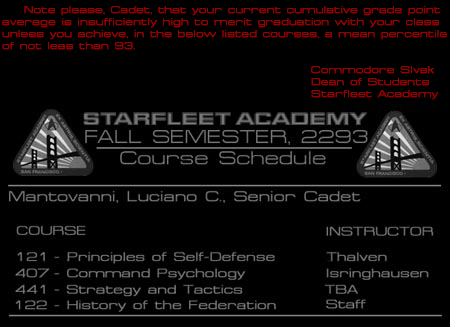

Luciano Mantovanni examined his schedule for the upcoming term—one

way or another his last at

…out of 317.

Upon hearing about this rather dubious distinction, fellow cadet Demora Sulu had attempted, in her

unique way, to be supportive.

“So what?” she’d said.

“Everyone in our class is pretty

damned smart. You don’t get into the

Academy otherwise.”

She’d realized her faux pas

an instant later, when he’d reminded, “I didn’t pass the entrance exams, Demora. I was

enlisted and received a field commission, remember? The orthodoxy have never been

fond of that. In many ways, I’m here on sufferance.”

Despite the setback, she’d retraced her steps admirably and tried

again.

“Somebody has to be

first, and somebody else has to be

last. There’s no shame in that.”

That time, he’d answered with a dryly amused, “How egalitarian of

you… Miss

Candidate-for-Valedictorian.”

Demora had reddened at that,

but kept up her effort.

“

Mantovanni had arched a brow and answered, “I’d guess they call

them a malpractice attorney.”

“No, smart ass,” she’d told him.

“They call them ‘Doctor.’”

His slight smile and subsequent silence had told them both he’d,

for then, conceded the point. Then, she’d made some crass but entirely welcome

comment about conducting a thorough physical on him; and since they’d been in bed at the time, one thing had led to

another (all of which he’d found far more

supportive), and he’d not thought about it again—until now.

The text currently on his comm screen, though, had just brought

his relative ineptitude back into focus:

Having already suffered through the math and science he so loathed,

Mantovanni had gone out of the way to make certain his last few months at the

Academy would be enjoyable ones, opting to save for last the courses in which

he was certain he’d easily excel; and, despite the warning he’d just received

from Dean Doomsayer, he was looking forward to a relatively easy term.

A 93 average for these courses? he thought.

In my sleep.

“Do you think you can simply sleepwalk through this

course, Mister Mantovanni?”

The student-teacher, Cadet Lieutenant Marc Stevens, had taken him

by surprise with that.

The class, thus far, had been more than easy; it had been

effortless. Mantovanni, for much of his life, had been the student of Sevek, greatest living practitioner of the esoteric Vulcan

martial art saraht kohl. Compared to that, Starfleet’s

eclectic hand-to-hand combat methods, especially at this introductory level,

weren’t exactly demanding. Still, he had quietly, dutifully learned the forms

and stances required, executed the moves with exacting precision, and patiently

endured lessons in both physical and philosophical discipline he’d mastered as

a child. He’d been more than a little bored…

…and, evidently, someone had noticed.

Mantovanni knew the proper, or at least preferred, answer in this

situation: A sudden stiffening to attention… an emphatic shake of the head… and

a frantically enthusiastic, “Sir… no,

sir!”

Yet, despite that awareness, he said nothing—which, in itself,

constituted a response.

Stevens was, in all ways, the prototypical alpha cadet—scion of a

wealthy and influential family, honors student, immensely popular with the

opposite sex (and not a few of the same sex, no doubt, had he been so

inclined)… an instinctual, hereditary leader. He expected results, and required

not only obedience, but a certain deference from his

subordinates… or, rather, his inferiors, as perhaps he saw them.

“I’m waiting,” he growled, “for an answer.”

Around them, class continued, but neither man had any illusions

about where everyone’s attention was now focused.

Mantovanni knew the situation might still be recouped, were he

simply to render some sort of conciliatory statement and/or gesture… but, for

reasons not entirely known even to him, made absolutely no effort to try.

As a matter of fact, he did just the opposite.

“I thought you were speaking rhetorically—considering how absurd the question is.”

Now the class stopped...

and, as one, turned to face the action. A few glanced around, seeking

Lieutenant Commander Thalven… but the Andorian had

evidently stepped away, leaving Stevens to run things for a few moments.

Amazing what could happen in a

few opportune moments.

Stevens possessed an excellent disdainful sneer, and employed it

now. “I don’t like your attitude, Mister

Mantovanni.”

An upraised eyebrow, though, countered it nicely. “I’ll be sure to stay up nights fretting about

that, Mister Stevens.”

In the instant before it could come to harsher words, or even

blows, Thalven announced his return with a sharp,

“The rest of you… forms practice, please.” He

commenced a purposeful stroll towards the two disputants, the merest of glances

here and there assuring that everyone was once again concerned with their own

business.

“Explain the nature of this impromptu convocation, please.”

Neither volunteered a word.

“Shall I interpret your silence as a reluctance to obey a

superior’s orders? If so….”

That spurred Stevens to respond with, “No, sir!” His eyes flicked

back to Mantovanni, before he offered, “This cadet’s mind-set needs adjusting.

I thought I’d tend to it.”

“And your preferred method was to wait until I’d given you charge

of the class, and immediately initiate a confrontation?”

Again, silence reigned… but Thalven soon

filled it.

“From this point on, you’ll limit your… mentorship… to making

certain Cadet Mantovanni is mastering what skills he must to successfully

achieve a passing grade—in this

course. Understood?”

“Sir! Yes,

sir.”

“Return to your duties.”

The Andorian cast his gaze out over the class, but Mantovanni could

nevertheless feel the weight of his regard.

“Feeling a little above it all, are we?”

Again, he chose to be unwisely candid.

“Even if I do, I never asked for preferential treatment.”

Thalven’s antennae reared, as if

in affront, and then reoriented on him.

“Didn’t you? You

requested a waiver for this course from the registrar… and when it was refused,

appealed to first the dean of students and thence Commandant Annalin himself. Are you perhaps unfamiliar with the

definition of ‘mandatory,’ Cadet?”

“Permission to speak candidly, sir?”

At the almost amused nod, Mantovanni put forth his case again,

succinctly.

“I have nothing to learn

here. My abilities as a martial artist are far in advance of what’s being taught. Forcing me to do this simply

in fulfillment of a requirement is illogical and counterproductive.”

The Andorian considered that, briefly.

“Your opinion is noted.

“Unfortunately for you, your

opinion and that of

Only now did Thalven turn to face him

again.

“Have I made the official position clear?”

Undaunted and unbowed still, the Sicilian met it.

“Flawlessly, sir.”

“Excellent.” His

entirely insincere smile faded. “As to your attitude with Stevens… he may be a

cadet lieutenant—”

“—and an elitist jackass.”

That interruption didn’t

score Mantovanni any points with the judge, either.

“As opposed,” Thalven countered, “to a

brooding, resentful semi-delinquent who should know better and have already

grown past this stage of post-teen isolationism? Your permission to speak

candidly is rescinded, Cadet,” he

added quickly, just before the younger man would have offered his opinion yet

again.

The silence held by a thread… but it held.

“As I was saying… he may be a cadet lieutenant…” he paused,

allowing another opportunity to interrupt.

This time, Mantovanni was prudent enough to forego it.

Thalven continued, “…but the

emphasis with him is still on ‘cadet.’ Even if the actual authority is

suspended until graduation, Lieutenant, you’re

still a commissioned officer.

“Act like one.”

Though the rest of class proceeded without incident, Luciano

Mantovanni now had the distinct impression that he was being graded on a curve…

…and that he’d taken it far too quickly.

***

Being caught between two worlds wasn’t a new experience for

Luciano Mantovanni. The first human raised on Vulcan, by a Vulcan, he had during much of his youth experienced the kind

of ostracism only that unique race’s people could impose—for a child,

intangible as a will o’ the wisp when he attempted to define or even identify

it... yet inescapable as the slender, unbreakable strips of an ahn woon. Anyone

who believed that logic had conquered all bigotry on that world had never found

himself on the receiving end of an insidious argument from a sadistic Vulcan

adolescent, in which he explained why humans were not only inferior, but in

many ways, little better than animals.

Most children, at one time or another, feel utterly alone; in many

ways, Luciano Mantovanni had been.

While such occurrences had not badly scarred him, they had shaped him… and his coping mechanisms, while effective, weren’t

exactly qualities that made one popular.

At the Academy, he’d once again found himself between Scylla and Charybdis—not precisely a cadet, yet no longer an officer…

and entirely welcome among neither group.

If it hadn’t been for Demora, he might

well have walked away… or, more likely, been none-too-politely asked to do just

that.

Of course, he hadn’t made it through yet, and the light at the end

of the tunnel might yet prove to be the proverbial oncoming train…

…or, more likely in this case, a torch held by the head of his

lynch mob.

Rarely did a Vulcan reach a state of noticeable unrest… yet, the

points of green adorning Cadet Suvak’s cheeks

indicated, at least to the trained observer, that his debate opponent’s

position had evoked an emotional reaction.

“Am I to understand,” Suvak inquired, a

hint of incredulity tingeing his tone, “that it is your position the Romulans

are culturally superior to the Vulcans?”

Their instructor formed his fingers into steeples—the classic pose

of intellectual superiority. Mantovanni, from his more emotionally detached

position, realized the gesture was a precisely calculated one… and it seemed,

amazingly enough, that the man’s calculations were correct.

After a measured pause, their teacher replied, “While Vulcans are, admittedly, highly influential in certain of

the Federation’s affairs, their effectual reach, in many ways, extends little

beyond Vulcan itself. Contrast it with that of the Romulans, who have built an

empire spanning thousands of cubic light years. The

Suvak appeared almost nonplused.

“Respectfully, sir… your reasoning is unsound.”

The target of that comment seemed amused.

“Really, Cadet? If so, you

have not demonstrated it during this discussion. The proof is in the pudding.

What criteria are we to use other than results? Indeed, by some measures….”

Kirk conducted a lively class, Mantovanni had to admit.

The only thing that would have made things better—nigh perfect—was

having it be the right Kirk.

Before them, though, stood Lieutenant Peter Constantius Kirk, nephew of the

Starfleet legend. He’d been teaching History of the Federation at the Academy

for over a decade now… and calling it a “survey course” had lured many an

unwary cadet into his classroom. They’d all left it a semester later; most of

them had even passed, as opposed to simply passing through… or, in at least one

notable case, passing out.

Kirk was continuing to hammer home his point.

“…the Pax Romulana,

to coin a phrase, holds greater sway than the Pax Surak.”

“Yeah… and Mussolini made the trains run on time.”

For a long moment Luciano Mantovanni wondered why, suddenly,

everyone in the class—including its instructor—had turned to stare at him.

Did I actually say that aloud?

“I take it, Cadet, you believe your upbringing and pedigree grants

a unique perspective on Vulcan… and, seemingly, Italian history? Please, enlighten us further.”

A few giggles followed.

I guess I did.

Suvak, from his expression, hadn’t

appreciated the interruption—especially considering its source.

“I do not,” he said,

with a healthy dose of the offhand disdain most Vulcans

master before age ten, “require your

assistance to support a position that is obviously

the correct one. If I may be permitted to continue…?” This last seemed

addressed to both Kirk and

Mantovanni.

The former, interestingly enough, said nothing.

The latter, predictably enough, didn’t echo that example.

“Suvak, you’re not mining insights.

You’re just digging yourself a hole.”

The resultant arched brow had little effect on Mantovanni. He

merely reflected it back on its source.

Not to be outdone, though, the Vulcan replied, “That, of course,

assumes you possess the intellectual ability to recognize insights when they are presented to you. Considering your

class rank and grade point average, that point is a debatable one.”

Oh, that’s it.

With a vicious lupine grin, Mantovanni began, “If you–”

“Gentlemen.” With a single word, Kirk regained the floor. “Since clearly you both have…” and he cleared his throat

before continuing with,

“‘insights’… as yet

unexpressed, both I and the class would appreciate you expounding on this

subject.

“To that end…”

Oh, God.

“…you two will collaborate

equally on a paper refuting my obviously ‘unsound’ reasoning: Fifteen thousand

words, which you’ll deliver to me two weeks from today. If, during your verbal

presentation on said material to the class, I get a sense one person did more

than his share, you’ll both fail.

“And I don’t believe either of you can afford that.”

No pins dropped. No cricket chirped. Still, the silence was

notable.

And then, wearing a cheerfulness that made Mantovanni want to

throw him through the transparent aluminum window-wall overlooking the South

Gardens, Lieutenant Peter Kirk, having just made a pair of his students’ next

fortnight an impossible one, said, “Now…

let us move on to the immediate consequences of the Earth-Romulan

War, shall we?” Without further ado, he launched back into his lecture.

Mantovanni and Suvak locked gazes.

Neither looked prepared to yield.

Actually… I’m more worried about

the Earth-Vulcan War, now.

I think it’s about to begin.

***

Static poured into the bridge, beat against Demora

Sulu’s head and set her teeth on edge. Perhaps the

overall effect wouldn’t have been so bad if she hadn’t known precisely what this particular sound foretold: In this

case, ignorance really would have

been bliss. Demora, after all, had heard it

before—just yesterday, in fact. Now, the subsequent anxiety and frustration

that had resulted, and which she hadn’t quite reconciled, returned to resonate.

This time, however, she didn’t worry for herself, but rather the

man who currently held command—not to mention her heart. And, knowing him the

way she did, Demora also knew that there was ample reason for concern.

Another blast of interference left the crew wincing.

“Clean that up,” Mantovanni

snapped, in a “don’t disappoint me”

tone she’d heard from few in her life— a tone that both galled and galvanized.

A captain’s tone, she

thought. How the hell does he do that when the rest of us sound like kids

wiggling around in a seat too big for us?

“I am trying, sir,” came

the response from comm, where the Tiburonian Javesh Krill sat and endured the blare of noise. With ears

like that, this must have been his idea of torture. Avoiding additional

discomfort, though, proved an excellent motivator, because “mess” abruptly

became “message.”

“…is the Kobayashi Maru… out of Altair

Six… –ck a gravitic mine… radiation l–… –gines disabled…”

While not exactly comprehensive, the gist was clear.

From the science station, Suvak

declared, “I am able to detect the vessel on long-range sensors, Captain.

Navigational subsystems place her at 321 mark 37,

distance 27,000,000 kilometers.”

Since the Vulcan had blithely stepped on her toes, their navigator, Michelle Madison, stomped right back.

“Science officer’s computations confirmed, sir.”

Demora suppressed a smile. Nice goin’,

Michelle.

Mantovanni gave no indication he’d noticed the sniping, but she

knew better, and silently wagered he’d somehow deal with it later—as if he

actually were their commander.

“Those coordinates are well

within the Neutral Zone, sir.”

Demora couldn’t say much more

than she just had without violating Academy honor codes, but she hoped that

he’d somehow take something useful from her inflection.

And it seemed he had.

“Don’t worry, Helm,” he said. “We’re not going in.

“Hold your course.”

Considering the whispers, that decision wasn’t to everyone’s

liking… but only one person actually spoke to it—loudly.

And exactly no one was surprised that Marc Stevens had something

to say.

“That ship is full of civilians… sir. We have a responsibility to safeguard them.”

“We also have a responsibility to maintain treaties the Federation

signed in good faith, Weps,” replied Mantovanni.

“Besides, it smells like a trap.”

Thank God, Demora thought.

“You can’t know that. May I remind the captain–”

Suvak interrupted the exchange with, “My

sensor telemetry on the Kobayashi Maru has ceased.” He studied his readouts further, and

seconds later added, “And I am now detecting three vessels crossing the Neutral

Zone border into Federation space.”

Son of a–

“

In silent response, the Vulcan touched at his console controls…

…and the image of three K’tinga-class battle cruisers filled the main view

screen.

Mantovanni frowned. “Informative, but… probably

a little too specific.”

“Some people,” Demora muttered, “are never happy.”

As one would expect, Suvak ignored the

chatter and continued supplying data. “They are on an intercept course and

closing at warp seven. At our current speed, we shall be within their weapons’

range in 43 seconds.”

“Subspace frequencies jammed, sir,” announced Javesh

Krill. “I can’t raise Starfleet.”

Mantovanni nodded; he seemed, in Demora’s

eyes, to be taking his own sweet time with critical decisions.

“Come about to 57 mark 32,” he finally

said. “Warp eight on my command.”

“Another three vessels de-cloaking directly ahead,” Suvak warned.

“Belay that last. Warp two evasive… ninety degrees down

angle… accelerate to warp eight after turn complete.”

Demora hastened to comply, and

the septet of Klingon ships slipped in behind, adjusting their velocity until

they were gaining yet again.

“Well… six against one,”

their captain observed. “No doubt that’s the Klingon definition of a fair

fight.”

This time, Marc Stevens managed to keep most of the dislike out of

his voice. “They’re deploying in a hemispherical attack posture—looking to

prevent our escape.”

Instead of answering, Mantovanni punched a series of commands into

his armchair controls.

“I now detect a third

trio of Klingon vessels de–“

Suvak never finished.

Even as Stevens cursed, “What

the Hell–?” the ship’s forward phasers lashed out, scoring hits on each of

the three cruisers even before they became fully visible. The full spread of

photon torpedoes which followed close behind left all of them spinning off

their perfectly conceived attack vector, trailing plasma and debris behind.

Amidst the chaos of cheers and chatter that followed, Demora Sulu heard Luciano Mantovanni

issue an order that made no sense to anyone but her.

“Bring us about,” he snarled.

“Now we’re going in.”

***

Within her first week at

She, however, knew the reality all too well—a reality that consisted

almost entirely of back-breaking labor repeated with mind-numbing regularity.

There really was nothing wrong with the simple life, per se—if you had simple desires, that is—but tilling earth just

wouldn’t do for the girl with the stars in her eyes: After hearing about

starships when little more than a toddler, no other career had seemed

desirable… and after actually seeing

one in Demeter Colony’s spaceport a few years later, none had even been

possible.

Eight-year-old Rachel had vowed, in that moment, then that she’d

give up anything, do anything, to

gain a place among the heavens; and to an idealistic young Federation citizen,

that meant only one thing—a spot at

Then, she had studied some more.

It had all seemed worth it, though, when the Graduating Class of

2297 (as they preferred to think of themselves) had been posted… and she’d made

the list.

Academy correspondence throughout the spring and summer of 2293

had contained the phrase “incoming freshmen,” and she’d grown to love it. There

was another word, though, she could have done without… and God knows, she’d begun to wonder after only a few days whether, in

some obscure, mean-spirited dialect, “

That word, of course, was “plebe.”

Almost all cadets fell into one of three archetypes.

First, and most common, were the rank-and-file. They’d arrive at

the Academy fresh-faced and eager, remember their time here as some of the most

challenging but rewarding years in their lives, and move on to their Starfleet

careers.

Next, you had the privileged, the aristocracy—what an irreverent

Presbyterian would probably have called “the Elect.” This category, in theory,

no longer existed at what purported to be an entirely merit-based organization…

but, in the real world, theory and praxis never does precisely jive. It

consisted of cadets who came from money or power—the kind of old money and

deeply-rooted power that both demanded and guaranteed a place in the graduating

class, followed by a favorable posting and rapid promotion. So long as one of

this ilk didn’t do anything criminal—well, at least

not egregiously and publicly criminal—their future in Starfleet was assured.

Finally came Rachel’s type—those who, if

they’d been a little faster, or a little homelier, or a little luckier, would

have escaped notice and plowed through their four years untroubled… or, some

might say, unmolested.

Rachel, however, was bright, pretty… and, having never traveled

further from home than Demeter Colony’s moon, Persephone, just a little

vulnerable.

And that was just the way Marc Stevens liked them.

In some ways, it would have been better for Rachel if she’d been

less perceptive and simply fallen head over heels… or, at least, once or twice

put her heels over her head. But, instead, when Marc had noticed her in Basic

Martial Arts and decided that she’d make a nice appetizer to begin his

senior-year reign, well… Rachel had proven an uncooperative snack. He invited

her out; she declined. He sent her flowers; she accepted them with a smile for

the delivery person… and, after closing her dorm room door, promptly threw them

away. She didn’t know why she didn’t like Marc Stevens. He was, after all, a

handsome, popular, influential senior.

She just knew that she didn’t.

Some men accept a polite refusal and immediately hone in on their

next target… or victim, if you prefer. Others try a different tack, and

actually attempt to befriend their potential lover.

Marc did neither. He was the kind of man who believed in Manifest

Destiny—well, his own, at any rate—and Rachel Carson was a frontier he’d

determined to cross…

…and conquer.

***

Few outside a certain loop knew it, but… the Kobayashi Maru scenario had, for years,

been a spectator sport.

There were those observers one would expect, of course: Teachers replayed

and analyzed the entire exercise, critiquing each often shell-shocked student’s

performance therein, exhaustively—pinpointing each misstep, whether technical,

tactical or philosophical… marking precisely where they’d gone wrong… how

they’d been defeated…

…and why they were now “dead.”

All that, however, was after

the fact… and the instructors, despite being the only individuals technically permitted to do so, weren’t

the only ones watching.

Certain interested (and, on occasion, uninterested but considerate)

parties always managed to let it be known when a group of particularly

promising cadets were about to face their Waterloo; and the knowledge

inevitably drew an audience to the Academy’s Faculty Lounge—where a simulcast

ran for as long as the cadets did. Usually, the entertainment provided proved

brief, but amusing.

On occasion, though, word would spread throughout campus, passing

through secret but long-established channels, of a group taking a direction no

one had before—giving the scenario a proverbial run for its money. Some of

Starfleet’s greatest captains had exercised their extraordinary minds and

spirits while failing brilliantly, even in some cases spectacularly… but

always, ultimately, failing.

The simulator itself had become progressively more realistic over

the years. Once, the mockup had been… quaint. Now, differentiating between it

and the actual bridge of a Constitution-class

starship was nearly impossible. In conclusion, whether you thought it turtle or

mock turtle didn’t much matter.

Either way, you ended up eating crow.

“When we grew up and went to school

There were certain teachers who would

Hurt the children any way they could

”By pouring their derision on everything we did

Exposing every weakness

However carefully hidden by the kids…”

- Roger Waters

Senior Cadet Mantovanni’s Kobayashi

Maru performance analysis began on a promising

note.

Unfortunately, what it

promised didn’t exactly bode well.

A pair of instructors awaited the dejected cadets as they filed,

practically slunk, into the briefing room. Both possessed lengthy experience at

the command level; they had, while evaluating Demora’s

stint in the center seat yesterday, played the traditional “good cop, bad cop”

roles… but had done it with such surpassing adroitness she’d never noticed

until well after the evaluation had ended.

Now came Mantovanni’s turn.

Without even bothering to replay the recording of their

performance, one demanded, “What the Hell

were you thinking, Mister? The Kobayashi Maru

had 57 officers and crew aboard, yet you abandoned them without even a token effort to assist.”

“I was ‘thinking,’ Captain Styles, that the Kobayashi Maru was a deception—that the Klingons had manufactured a compelling sensor ghost in

order to lure my ship into their territory.”

Demora gauged reactions to

that around the table, and across the board. With two exceptions, the other

participating cadets remained carefully expressionless. She couldn’t really

blame them; their turns would eventually, inevitably come… and considering how

well their “captain’s” review had thus far proceeded, drawing premature

attention to oneself seemed masochistic at best… and at worst, downright

stupid.

The Vulcan Suvak had arched a skeptical

brow at the revelation Mantovanni thought the Kobayashi Maru chimerical. That reaction

made perfect sense, though: if true, such would mean that his own analyses and

conclusions had been incorrect… and most of his people didn’t take at all well to such a perspective.

Marc Stevens didn’t even bother to disguise his glee at what had

immediately become a vivisection.

One thing was certain: The two instructors wielding the knives

certainly didn’t seem reluctant to keep cutting.

Demora had lost the thread of

conversation—or, rather, condemnation—and fumbled to recover.

“–at argument holds very

little water, if any at all,” Commander Rodgers was saying. “While hunches are a command prerogative, Mister

Mantovanni, such is hardly applicable inside a simulator. You can’t have an

instinct about a situation that isn’t real world.”

Hell, she thought, this time it’s

“bad cop, worse cop.”

There was, at that point, a relative lull in the barbeque: The

instructors let Mantovanni baste for a time, and moved on to review the other

cadets’ performance.

Demora watched him

surreptitiously, to no avail: His expression was so guarded even she, who knew

him better than perhaps anyone else on Earth, had no idea what he was thinking.

The timbre of Mantovanni’s voice had remained even throughout the initial

review, but its volume was decreasing with each exchange… and that wasn’t a good thing. She knew Styles

thought he’d cowed this presumptuous cadet into accepting his fault and

failure… but she understood her lover well enough to predict that round two of

the debriefing was likely to be far more… eventful…

than round one had been.

It began without warning.

“Do you understand your missteps and errors in both tactical and

ethical judgment, now, Cadet Mantovanni?” asked Rodgers.

Oh, no.

“Permission to speak

freely, sir?”

“Denied,” Styles

snapped.

For the second time in as many weeks, Mantovanni’s determination

to have his say nearly shattered the chains of protocol. Again, though, he held

his tongue.

If not his temper, Demora thought.

Still, he made his feelings known.

“Then I have nothing further to say on the subject.”

That, however, was not the

sought-after answer.

Styles reiterated, “I believe you were asked if you understood your errors, Cadet.”

“No,” answered Mantovanni. “I don’t believe I do.

“I don’t understand why avoiding an obvious trap is an error. I

don’t understand why fighting a brace of Klingon cruisers to a virtual

standstill for 37 minutes is an error… and I certainly don’t begin to understand

the point of this entire exercise—other than to frustrate students, and

subsequently berate them for their honest and sincere efforts.”

He addressed the other cadets. “The Inquisition here can say

whatever it likes. You acquitted yourselves well, and I’m proud of you.”

His unmitigated insolence had earned him a few seconds of shocked

grace, but it receded in the face of outrage.

Styles looked close to apoplexy. For a minute Demora

thought he might actually smack the desk with his ubiquitous riding crop, but

they were spared that, at least.

“That’s enough, Cadet!” he declared. “You may consider

yourself fortunate that your insubordinate tone and statements have earned you

nothing more than a permanent reprimand in your file. It could have been much

worse… and still can if you say another

word.”

Please, God, Demora offered fervently, strike him dumb for a moment if you have

to… but keep his mouth shut.

Due to either her faith in the Deity, Mantovanni’s sense of

self-preservation, or some amalgam of both, her prayer was answered—for all the

good it did.

“As for the rest of you…

“…the results of this scenario will be appended directly to

your final grade point average with the weight of a full semester course…” He

spoke over the subsequent disbelieving groans and gasps. “…as they have been since the test was instituted. No one is

picking on you, Cadets. Consider it a pop exam, if it helps—a little taste of

the unpredictable that is part and parcel of life in Starfleet.” Styles then

refocused his attention on the afternoon’s “star” pupil.

“Needless to say, Mister Mantovanni, you’ll be receiving an ‘F’ on this one.”

He had clearly enjoyed announcing that last.

The rest of the briefing no doubt occurred… but Luciano Mantovanni

would have been hard pressed to repeat a word of it.

It

counts how much? he thought.

How

much?!

Mantovanni calculated feverishly, almost frantically, weighing his

failure here, and the fact that it would be factored

into his grades, against what he knew to be his personal minimum requirements

for graduation.

Then, he did it a second time… and, finally a third—with the same

result.

I… I can’t pass. No matter what I do from now through

finals…

…I can’t pass.

This time, Demora, to her complete astonishment,

saw his face change.

It wasn’t glaring, but between one moment and the next, Mantovanni

had come to some realization… and whatever it was had shaken him—nearly shattered him.

And when minutes later they were dismissed, he practically fled

the room, moving so quickly that by the time she’d reached the hallway…

…he was lost to sight.

For a few moments, Mantovanni debated simply packing his few

personal effects and catching the first available transport to Vulcan… but

then, as his heart slowed and his mind cleared, he decided against that.

He had two more classes that afternoon. He headed for the next one

with new purpose.

They may have flunked me…

He grinned… and it was not a pleasant sight to behold.

…but that means I have nothing more to lose.

***

Demora Sulu

spent the afternoon on her lover’s trail… or, rather, in his wake. Twice that

afternoon, she rushed from a lecture hall, gauging what she thought would be

Cicero’s most likely route after his own classes and hoping to thereby

intercept him; and twice that afternoon, she missed him… or, maybe, he eluded her.

After her first failure, Demora thought

that perhaps he’d stayed late in Basic

Martial Arts, and headed there, only to find a knot of students still

standing in the studio’s midst, jabbering as only knots of students can. A

quick glance confirmed that all present were plebes… and Demora

wasn’t, at the moment, feeling very

charitable. One of the five spotted her approach, hissed a warning to the

others… and the quintet was at rigid attention even before she reached them.

“As you were,” she

ordered, and they relaxed—minutely.

“I’m looking for Senior Cadet Luciano Mantovanni. Do any of you

have an idea where he headed from here?”

“No, ma’am,” they

chorused, a bit too eagerly.

Demora waited and watched.

Each of them looked to be on the verge of adding something; yet, ultimately,

all chose to remain silent.

I don’t think so. She dredged

her memory… and then scared the crap out of them.

“You… Cadet Morris.”

The lad cringed, dismayed that she somehow knew his name, but stepped forward with a fair

approximation of gameness.

“Ma’am! Yes,

Ma’am!”

“You look like the

verbose sort, Mister Morris. What are you all bursting, but lacking the nerve,

to say?”

In later years, Captain Demora Sulu would hear it rumored that she was the daughter of

both Admiral Hikaru Sulu… and a mysterious beauty from a

little-known race of telepaths—little reckoning that the legend of her uncanny

perceptiveness had started at this very moment.

For now, though, she was simply happy to get Morris talking.

“Well, ma’am… you just

missed him.”

“So did Stevens,” muttered

another, much to the dismayed amusement of the others. They looked like they’d just

laughed aloud at a funeral… and realized that, considering the company, it

could well have been scholastic

suicide.

Demora swept them with her

glare, and the giggling ceased.

“Well? I’m waiting, Cadet.”

Morris, despite his unease, told a pretty good tale.

“We were supposed to spar today, Ma’am—traditional three-point

bouts for current class rank. Cadet Stevens–”

“Please dispense with ‘Cadet’ after every name, Morris. We all

know their status here.”

“Uh… sorry, Ma’am. Um… Ca– uh, Stevens asked for a volunteer to demonstrate the

rules and protocols of such a match, since most of us had never done it.”

“And still haven’t,” came a voice from behind him.

Ignoring the comment—and from his expression, desperately hoping Demora would, too—Morris continued.

“Mantovanni raised his hand… and, let me tell you, Stevens looked

like God had showered him with manna in the desert.”

“‘By all means,’ he

said.

“Well, they entered the ring, bowed…

“…and Stevens was across the space between them almost before it

started. He’s fast.”

The same commentator helpfully added, “Yeah… Academy Martial Arts

Champion two years running. It’s why he’s student-teaching this semester.”

A third cadet shushed him.

Morris resumed his account.

“From what I could see… I don’t think Stevens was exactly looking

to score points, even in the

beginning, Ma’am.”

A murmer of agreement supported his

opinion.

“That first kick he threw was the kind that deposits someone in

the next county… or the next solar system.”

Oh, my God.

“But it missed.

“Mantovanni slipped it, and slid away—with Stevens in hot pursuit.

He started throwing punches, kicks and even a few leg sweeps. His form was

perfect… well, I mean it looked perfect to me.

“Yet… he kept missing.”

Demora blinked.

“What?”

“Mantovanni was never quite

where Stevens was aiming, Ma’am. Mantovanni slipped some blows… deflected

others… evaded a few more entirely… but Stevens wasn’t actually landing any.

“I’m not sure, Ma’am, but I don’t think these kinds of matches

have rounds, per se. The two combatants just have it out until one or the other

scores a point, then start again until somebody

reaches three.”

“You’re right, Morris,” Demora supplied

absently. “What happened next?”

“Well...” he said,

and hesitated.

“Well?” she prodded.

“More of the same, Ma’am.

“It wasn’t a fight. It wasn’t even like Mantovanni was… I don’t

know… counting coup… because, other than blocks, Stevens never touched him… and he never touched Stevens.

“It felt more like he was… expressing contempt, somehow—like he

wouldn’t even give Stevens the satisfaction of getting knocked down… or out.

“And it just went on… and on… and

on. After about ten minutes, Stevens was a little winded. After a

half-hour, he was sucking air like there wasn’t any in the room.”

“The ol’ rope-a-dope,” said a young

female cadet who until then had been silent. At the five blank stares, she

sighed explosively. “Don’t you people know

anything? Ali-Foreman? The

Rumble in the Jungle? The Perfect Punch?” Her voice acquired a nasal twang, and

she intoned, “‘One

of the greatest exhibitions of strategic pugilism it has ever been my pleasure

to wit–”

Upon remembering her audience, she stopped.

“Uh… sorry.”

“Where was your instructor,”

Demora asked, “while all this was happening?”

“That’s just it!” Morris exclaimed. “He was here… and he never did a

thing to stop it!”

Their boxing expert chimed in again.

“Exactly what was he

supposed to stop? Nothing happened.”

“Stevens got humiliated,

that’s what happened,” Morris

countered. “I felt sick to my stomach just watching it.”

“And why didn’t he

stop?” asked Demora.

“Huh?”

“Why didn’t Stevens

stop?” she reiterated. “From what you said… all he had to do was step back, and

it would have been over.”

A long moment of silence followed.

“Oh, man… she’s right.”

Morris finished his account.

“Well, eventually, he just… ran down, like a mechanical toy that

hadn’t been wound. Mantovanni waited until it was clear Stevens wouldn’t and

couldn’t throw another punch… and then left.”

Demora frowned. “Left the

ring?”

“No… left the room.

“Commander Thalven spoke very quietly to

Stevens, and they left together, about 15 minutes ago—just after Mantovanni.

Stevens could barely walk, he was so tired… and he looked…” Morris trailed off,

and never finished.

It wasn’t necessary.

Demora made it to her next

class with seconds to spare, but didn’t hear much of what was said there. Her

thoughts were elsewhere.

Without a blow… without even a word… Mantovanni, as always, had made his point.

She wondered how many more he had to make…

…and to whom.

***

The current guest in Peter Kirk’s office wore a poker face—one

which implied only that, when playing said game, he usually won—and listened.

“The discussion turned to command decisions in critical

situations—something I told him was better addressed in Lieutenant Isringhausen’s class—but he had a point to make… or an axe

to grind.”

“And I take it he said something you didn’t like.”

“A few somethings,” Peter replied.

“Why didn’t

Peter Kirk asserted, “The situation was more

complex—psychologically and

tactically speaking—than you realize, Cadet.

“And that’s Captain Kirk

to you.”

Mantovanni snorted.

“Oh, now, there’s an

unbiased perspective: Captain Kirk’s

nephew defends Captain Kirk’s

actions. Well, I suppose I can’t fault your loyalty.”

Peter restrained his first reaction, barely. This young man had a

way of provoking people that had even upset the Vulcan Suvak

some days before. He’d known that… and yet, still, Mantovanni had gotten one in

under his sensors.

He steadied himself internally, and then answered.

“It’s my job to provide

an impartial viewpoint, Cadet—even on subjects that are near and dear to me.

The Academy trusts me to do that. Perhaps you should, too.”

The target of his mild chastisement actually laughed aloud,

cramming undiluted disdain into the sound, before giving an opinion on that.

"Oh, Mother of God...

do you really

think you'd be an instructor here if you weren't the Golden Boy's nephew? Please... right about now you'd be

getting rejected for tenure at

“Oh, my goodness.”

Peter smiled.

“Yeah. That was pretty much the reaction in class, too.”

His visitor exhaled slightly. “What did you say?”

“Let me recall… oh, yes.

If memory serves, I said, ‘Get out.’”

“Should I assume ‘you snotty little bastard’ was implied?”

That helped, for a moment. Peter chuckled, and conceded, “It was a first-rate insult.”

The other man nodded. “Seems like he’s damned good at hitting

people where they live…” He cocked a knowing eye. “…even if they shouldn’t be living there.”

“Point taken,” Peter allowed. Then, he added, “Afterwards, he was waiting for me here…

“…and it wasn’t to apologize.”

***

Demora announced both her

presence, and the imminent argument, by first barging through and then slamming

behind her Mantovanni’s dorm-room door—hard enough to shake the old-fashioned

glass in its windowsill, rattle the pieces on his 3-D chessboard… and roll his

eyes.

Blessed Madonna, here we go.

Her tone started off accusatory… and got worse from there.

“I heard what you did in Peter’s class, and in his office,” she

seethed. “I heard what you said. Jesus, half the campus heard you both!

“How dare you repeat those stories about Captain Kirk I told you!”

With an infuriating cool, he replied, “You never asked me not to.”

“That’s a God-damned technicality! I revealed all that in

confidence, and you know it!”

Mantovanni arched a brow, and countered, “No doubt the same

‘confidence’ with which your father told you?”

Her furious blush let him know that, as usual, he’d struck

unerringly.

“You know… you don’t just

burn your bridges behind you, do you,

He stood to face her.

“What precisely would

you like me to say at this point—that I’m sorry

The Sainted One took some hits? Well, I’m not, so that’s not going to happen. That glorious marble effigy of James

Kirk most people have built up in their minds could stand to have some pigeon shit dropped on it. I didn’t say anything that wasn’t true… or that

shouldn’t have been said a long time ago.”

A flare of regret washed over him as, for an instant, Demora Sulu looked on the verge

of tears.

“I trusted you,” she

whispered.

For that betrayal,

Mantovanni knew he should apologize; but then he remembered that Demora, at least, could simply talk to the right

people—including a Kirk or two—and her life would soon afterwards again be

smiley faces, good grades and a bright future.

He, on the other hand, would be gone either way.

So, instead, he murmured, “‘A

little taste of the unpredictable that is part and parcel of life in

Starfleet.’”

And instead of reacting with repentance or even anger when she

slapped him, Mantovanni smiled slightly… and presented the other cheek.

Demora gently shut the door

behind her… and the resultant “click” seemed almost to jar him awake. Suddenly

torn, he debated giving chase for almost a minute… sighed in relief when a

gentle knock told him she’d returned… opened it…

…and found himself face-to-face with James T. Kirk.

***

Like most Starfleet installations (and despite its proximity to Fleet

Headquarters), the Academy had its own transit station, housing both

transporter and shuttle platforms. These were, as one might imagine, neat,

well-lit, clean, efficient, and usually bustling with activity—everything you

might expect from such a facility.

One thing, though, had survived the centuries that separated this version of such a place from its

earlier analogs: That indescribable feeling of being there in the middle of the

night—waiting. “The bus station blues,” someone had once called it—a unique

hopelessness that sometimes set in even if you anticipated a happy consequence

to your vigil… and always set in if

you didn’t.

It had already claimed Rachel Carson… and she hadn’t put up much

of a fight.

She sat on a bench facing the Departures

board, slumped against her bulging duffel bag. Someone would have undoubtedly

noticed how still she’d been—if anyone else had actually been present, that is: At Starfleet Academy,

a time like 0245 hours with classes scheduled at 0800 that morning didn’t see

many people leaving. The only other individual in the vicinity, a nameless and

disgruntled ensign manning the transporter, had, when she’d entered, curtly

nodded… and then, promptly, nodded off.

Rachel tried hard not to think and, when that failed…

…tried harder not to cry.

WORK ON THIS STORY HAS BEEN SUSPENDED, AND WILL

PROBABLY RESUME IN SUMMER/FALL 2006